TEXTS/ARTICLES

Article published to coincide with Point to Line to Particle at the Beacon Museum,Cumbria,UK. 2022.

Why the drawings look like they do: specific connections to the concepts of particle physics

Drawing is a legitimate and effective tool of enquiry able to create powerful and high-quality outcomes and how a serious attempt to find equivalents between the visual language of fine art and the scientific language of the standard model can be made. This parallel visual world is intimately related to the sub-atomic realm creating a continuum between disciplines, bridging rigid definitions of what is considered art or science allowing the creation of a new language with which to explore the complex hidden world around us.

Pure visual elements

Paul Klee encouraged modern artists to work with pure elements of the visual language free from extraneous ideas and concepts. Constructing the work using the elemental building blocks and principles and only at the appropriate time should additional concepts such as portrait, or landscape emerge. If it happens at all it should be a by-product of the “forming” processes and not the reverse. I have tried to maintain a pure elemental quality to my visual language to create and sustain the equivalence to the elemental particles which through their interactions create all forms of matter and indeed what we term “reality.”

Democratic diagrams and the pen

Initially I developed a technique of diagrammatic drawing, democratising mark-making, freeing it from the need to “make art.” Searching for equivalents not expression made drawing available to my scientific colleagues familiar with Richard Feynman’s diagrammatic “depiction” of particle interactions which are ubiquitous when speaking with particle physicists. Therefore, I often use simple pen and ink technique as the pen is an implement that can be picked up from any office desk and carries no connotations with the making of art to distract.

Whether in the cosmological “line walking” of Paul Klee, the diagrams of Richard Feynman depicting particle interactions as a guide for calculation or the particle recognition training manuals of Enrico Fermi the diagrammatic line is the mode of realisation.

Stripping back to basic purer visual elements naturally brings you close to the diagrammatic; combined with the transition from expression to equivalence allows a form of “diagrammatic drawing” to naturally emerge.

In western art perspectival dominance was shattered by modernism linked to scientific discoveries that resulted in quantum mechanics. Feynman diagrams are the opposite of vanishing point perspective that enforces a decision regarding the single viewpoint. Each diagram is one of many possibilities that together make up “the sum over paths” necessary to calculate the probabilities.

The field

A basic connection between drawing and particle physics is the idea of “the field”. Artists have always been aware of the picture plane but from the early 20thcentury onwards it became the visual field and no longer required reality to be depicted by the static single eye. Indeed, it could now lie horizontally as well as vertically. Leo Steinberg in “Other Criteria” credits Robert Rauschenberg with the introduction of the “flat-bed picture plane.” This is mirrored in science by the development of James Clerk Maxwell’s field equations and quantum field theory where every particle is considered an “excitation” of its field and some obtain mass through interactions with the Higgs field.

Use of templates

Marks and gestures are chosen in response to particle characteristics and interactions, and these are partially formed by making marks against prepared templates that “interact” with the pen during the drawing process. Rhythms and gestures are laid down and then worked into as events manifest themselves in the visual field. This process cannot be completely controlled referencing the random nature of reality at the quantum scale. (Where there is only a probability of something happening, perhaps with a high percentage of likelihood but it cannot be considered a law.)

This allows the interaction of two different systems. One set of marks and gestures developed in response to the particles themselves, (leptons, quarks and bosons) and their characteristics, (spin, mass and charge) interacting with another set developed in relation to the various form of particle interactions with the forces. (The strong force confining quarks, particle decay and transformation via the weak force etc.)

In the early 1950s to the late 70s templates were used by the human “scanners” to analyse photographs from the detectors attempting to identify the particles involved. Therefore, their original use was the detection and identification of existing tracks. My use of templates is to produce new “equivalent” marks, tracks and traces through the medium of drawing.

The templates also reference the magnetic fields in the Colliders which control and focus the path of charged particles as they are accelerated prior to collision or keep them within a detector long enough for their tracks to be measurable.

When drawing -

I am involved in the search for equivalents between the graphic elements of point line and shape and the particle characteristics of spin, mass and charge and the idea that particles are not tiny spherical objects but rather spread-out waves or fields which during interaction exhibit particle-like activity. The work explores the idea of interaction and movement of the drawing media attempting to find connections between the “visual field” and the quantum fields of the various particles.

I have introduced the use of templates that “interact” with the drawing process in different ways as particles interact via the fundamental fields and forces.

The three main graphic elements of point, line and shape, their qualities and uses are utilised. Points can be static, but clusters can suggest a subtle form emerging or disappearing perhaps giving ideas for representing the elusive particles. Unlike points lines have directional energy. Varying the thickness and tone of line can establish equivalents in particle physics terms to mass. Arrangements of thicker, darker marks more densely packed contrasted with light, thinner marks in spacious arrangements can be executed to explore differences in the mass of selected particles.

Whether the tonal development is placed, either within the boundary of the emerging shape-particle or around the outside references the artistic idea of positive and negative shapes and this creates connections with the positive and negative electromagnetic charge of certain particles with shapes defined by simple lines considered neutral.

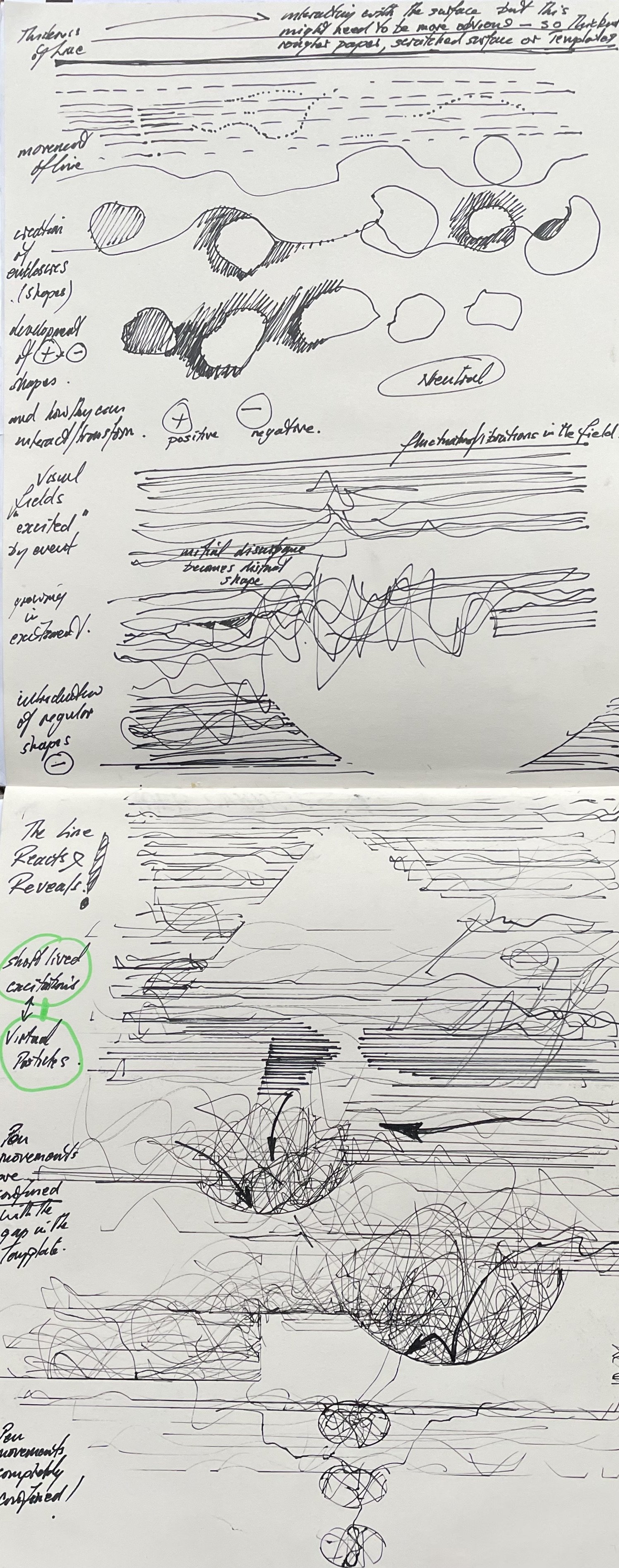

Fig1. Excitations within the visual field, the “Particle-shape” emerges.

Fig 2. Excitations within the visual field and the “Particle-shape” emerges that is negatively charged as the shape is the negative “gap” area.

Figure-ground Positive-negative Wave-particle

Fig3. Equivalents between the positive and negative shapes, (figure and ground) and electromagnetic charges, positive and negative and neutral of the particles.

The relationship between figure and ground in artistic terms is analogous to the wave - particle duality in quantum mechanics. The paper or support for a drawing is never considered a vacant background against which elements are seen; rather it is a visual field with “potential” from which they emerge just as a particle’s location can be thought of as an “excitation” of their particular field from which it emerges through interaction.

The manipulation of the figure-ground relationship enables visual elements to manifest themselves in the field and those configurations can be developed further by the manipulation of either the positive shapes or the negative surrounding areas referencing the positive and negatively charged particles. This can be additionally tonally manipulated allowing heavier or lighter visual density to reference the mass of the particle. They can also have a particular alignment in the field referring to the quantum quality of spin-up or spin-down. This highlights the intimate relationship possible between figure-ground, positive-negative and the particle and wave-field.

Graphite / Frottage

A wider range of drawing materials was utilised as my collaborator became more comfortable with the production of artwork. This included the use of graphite, not only as a pencil but also in stick form enabling rubbings to be made over the templates that were now placed under the drawing surface. The graphite interacting with the uneven surface created by the templates beneath. Areas of light and dark tone emerge suggesting various positive and negative shapes. A rough / smooth contrast emerges through the strokes of the graphite and the emergent particle- shapes are textual in nature. These textural qualities suggest particle - shapes not yet entirely formed or already starting to decay and change.

Air brush / spray technique

The templates are now placed on top of the drawing surface and now act as “masks” interacting by obstructing the spray technique.

The introduction of the airbrush was driven by three factors, firstly a reference to the probability cloud of particles rather than a definite location that is implied by drawing with graphic pens. Electrons do not orbit the nucleus of the atom in clear pathways but in a “cloud” of probabilities. The spray not only contrasts with the sharp line of the pen but also reflects the uncertainty of determining the position of particles until interaction causes the “collapse of the wave function.”

Secondly the spray involves a myriad of tiny dots being fired at the paper surface, an “automatic pointillism” which can be made more obvious using a coarser spray and referring to the basic visual element of points in relation to line and shape. It is also references particles being fired at various targets during experiments and the famous “double slit” experiment with particles fired at a barrier with two openings used to demonstrate wave-particle duality following analysis of the interference patterns.

Thirdly the positioning of objects on top of the drawing surface that are then sprayed around represents the idea of a three-dimensional object being a projection from a higher fourth dimension.

Therefore, I have 3 main media, techniques and approaches-

Pen – Line, directions, drawing against various selected templates. The moving line interacts with, is guided by or is confined by the chosen template.

Graphite – tone, area, the use of rubbing / frottage. Templates placed beneath the drawing support and the graphite “rubbed” across the uneven surface interacting with the templates beneath. Areas of tone naturally result in contrast to the lines with significant additional textural qualities introducing a rough / smooth contrast.

Spray - the use of airbrush / spray. This technique interacts with the templates as “masks” that are sprayed around. An added quality is that when wet, the masks can be used to print from which naturally reverses the positive / negative relationships.

Fig 4. Use of templates “interacting” with the pen and influencing the type of marks made.

Fig5. Using the template beneath the paper and rubbing the graphite over the irregular surface for the frottage technique. The particle shapes naturally appear through the process with positive and negative shapes.

The line reacts and reveals

Fig 6. The Line reacts and reveals

Some of the initial drawing elements and their possible equivalents to the particle interactions within the fields.

From top to bottom we see initially the simple line, then variations of line, different thicknesses, darker to suggest more mass or broken and less visible to suggest barely any mass at all.

The movement of line with a direct urgency or meandering with less energy, the creation of enclosures sees a crude form of shape emerge as particles-like elements.

These “particles-shapes” can be given positive and negative charge depending on where the tone is developed on which side of the enclosure, in artistic terms the positive or negative shape can be developed.

Artists also refer to the positive and negative shapes as the the “ figure - ground relationship” with the figure being the emergent shape and the ground being the field from which the figure emerges. It is worth stressing that it is the interrelationship between figure and grounds that creates the composition and therefore the ground is as crucial as the emerging figures.

Lower down we see how the visual field can equate with the quantum field of particles and suggestions as to how those fields can become “excited “and produce further particles- like activity.

At the bottom of the diagram chart, the use of templates which interact, guide and confine the movement of the line.

Fig 7. Examples of the 3 techniques and approaches with specific outcomes described. From left to right 1) pen marks reacting to a template that confines the marks within shapes. 2) rubbings with graphite with the template underneath the paper producing both positive and negative shapes. 3) Spray paint using the templates as masks creating an interplay between positive and negative shapes, dark positive circles and hexagons leave negative linear gaps but when larger groups of hexagons/circles are used the “gaps” of the lines become positive and the shapes seem to become the dark negative ground. All show a visual field in which excitations and fluctuations are occurring.

Fig 8. Examples of the 3 techniques and approaches with specific outcomes described. From left to right. 1) pen marks reacting to a template that produces circles that are developed as mostly positive but with some negative shapes/charges. 2) Rubbings with graphite with the template underneath the paper producing radiating rings of both positive and negative shapes. 3) Spray paint using the templates as masks creating gradations of tone suggesting movement and/or a gradual increase/decrease in energy. All studies show a visual field in which excitations and fluctuations are visible.

All is movement and connections, but line can catch it

Leonardo da Vinci, in his Treatise on Painting states,” The secret of the art of drawing is to discover in each object the particular way in which a certain flexuous line, it’s generating axis is directed through its whole extent.”

John Ruskin in The Elements of Drawing states “Try whenever you look at a form to see the lines in it that have power over its past fate and will have power over its future… those are their fateful lines.”

Paul Klee in the Bauhaus lecture notes The Thinking Eye talks continually of “taking a line for a walk” and different energies that the line can have as it changes and evolves and creates enclosures and more complex rhythms and shapes.

Ruskin also talks about change and movement throughout and across vastly different timescales, fleeting and geological. “The movement of animals, the tree in its growth, the cloud in its course, the mountain wearing away,” and the importance of “knowing the way things are going.” All is change and should be drawn so.

Physicist Carlo Rovelli states that the quantum world describes “things not as they “are” but as they “occur” and interact. A world not of objects but of events.” Reality in its smallest state seems to involve a constant choreography of particles and fields.

Line takes us back into thought processes and the relationship between the conscious and unconscious. Because if drawing is a technique suited to revealing unconscious processes, then line of all the basic visual elements is the most direct means of accessing those processes.

Stanley William Hayter, a British printmaker associated with the Surrealists in Paris and the abstract expressionist in New York originally trained as a scientist studying chemistry. In a short essay on automatism “Of the Means,” published in the abstract expressionist manifesto “Possibilities” immediately preceding Jackson Pollock’s “My painting” statement, says “Of all the means by which the unconscious functioning of mind can be made visible line has become so completely normal and acceptable that it’s specific character is easily overlooked.”

Jonathan Allday in his book, Quarks, leptons and the big Bang states “Quantum objects can more accurately be talked about as a set of connections and relationships rather than a set of fixed properties.”

The energies active at the quantum level is reflected by Kandinsky in his book “Point to Line to Plane” where he describes the equivalent violent of one visual element turning into another,

“…this force hurls itself upon the point, which is digging its way into the surface, tears it out and pushes it about the surface in all directions, the concentric tension of the point is thereby immediately destroyed and as a result it perishes and a new being arises which leads an independent life in accordance with its own laws. This is the line.”

David Bohm proposed the development of a new language that shifted the emphasis away from a division between object and subject towards a more “verb-centric” approach centred on action and movement. He maintained that reality and knowledge must be considered as a process. Division in thought is reflected in division in language and therefore both are fragmented. Yet reality at the quantum level reveals that the elementary particles are on-going movements, mutually dependent because ultimately, they merge and interpenetrate. Language should describe actions and movements flowing into each other, merging without sharp separations or breaks. Movement is a primary notion, while apparently static and separate existent things are relatively invariant states of this continuing movement. Therefore, we require a new language or mode of expression “the rheomode” or flowing mode that breaks down the subject- object division and fragmentation, a new language to reflect the new reality.

Article published in Printmaking Today, volume 30, issue 118, by Sarah Bodman, Senior Research Fellow for Artists' Books, UWE.2021.

His Dark Materials

Ian Andrews talks to Sarah Bodman about his collaboration with a particle physics group resulting in artists' books exploring dark matter.

Ian Andrews is developing a new series of books about the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). These form part of an ongoing collaboration with Prof. Kostas Nikolopoulos from the particle physics group at University of Birmingham (UK) who is currently impatiently waiting for the LHC to come back online after its upgrade to achieve the higher energy levels needed to search for the phenomena of dark matter. Whilst the LHC is inactive Andrews has been researching 'earth pigments and naturally occurring radioactive material so that the drawingsabout matter are made from "stuff" that actually involves a form of particle interaction, radioactivity.'

Andrews speculates on 'what traces dark matter might leave. My work is based around the hand-drawn mark and the residual printed trace. I use masks and templates to draw and spray against and take impressions from these when still wet. The books use a monoprint-like seeping of white ink through black pages.' This references cloud chamber images from late 19th-century detectors invented by CTR Wilson, originally to study atmospheric effects in his laboratory, which inadvertently showed subatomic particle trails.

Andrews admires the ‘Feynman diagrams’ invented by theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, to help visualise interactions for mathematical calculations. These diagrams of the behaviours of subatomic particles identified the necessary calculations to "make the invisible visible" as inspirational examples of the links between drawing and scientific enquiry. Paul Klee's Bauhaus lecture notes (The Thinking Eye) provide a practical example of how to strip my practice back to the elemental elements of point, line and shape. I search for connections between them and the elemental particles characteristics of spin, mass and charge and the interactions between particles that are a constant choreography of transformation.'

Andrews continues, 'My response to quantum mechanics is a serious effort to understand it, visualise it and find equivalents between the elemental language of drawing and particle interactions, something verifiable where Kostas could say "yes I can understand why that set of marks is being used."

For me it has become an opportunity to reconnect with visual forces in the language of drawing, with Kostas given a way in to understanding my work. This has encouraged greater rigour in my thinking and I have been intrigued by his surprise that I don't learn everything I can, and then when I understand —make the drawings. As an artist, I can make what I consider finished legitimate statements in drawing terms with varying levels of scientific understanding.'

The drawings speculate what traces dark matter might leave. 'Despite the success of particle physics research over the last 100 years, culminating in the standard model, unfortunately this only accounts for 5% of what is out there, the rest is dark matter and dark energy. Dark matter is so called because it doesn't interact with visible light so any visualisation is a fraud in a way. It does interact with gravity so the leaking through of pigment refers to this, and as less traces of ink make their way through to deeper pages, so less information is retained — referencing the difficulty in finding dark matter and how we only see indistinct traces from which we infer its existence.'

Alongside exhibitions of the drawings and artists' books, Andrews and Nikolopoulos run practical workshops for schools, colleges and adult groups. 'We use techniques from the visual arts to help explain complex quantum phenomena and champion a dialogue between art and science. Participants experience drawing, photography, sculpture and performance introducing them to particle physics. Prof Nikolopoulos also works with dancer/choreographer Mairi Pardalaki and was awarded the European Research Council's inaugural public outreach award for his work with Maki and myself.'

Andrews says, 'Each book is usually on the go for several months. There can be considerable gaps in the time spent working on them, time for reflection and more research; they become a collage of thoughts and levels of understanding. They have to be long enough to reflect the amount of data that needs to be collected at the LHC before discoveries of new quantum events can be announced. At first the work resembles coded information or modern graphic notation. Marks and gestures are chosen in response to particle characteristics and interactions and these are partially formed by making marks against prepared templates that interact with the pen during the drawing process. However now it feels that because tremendous forces are operating at the quantum level, I need to utilise a more vigorous manipulation of "matter" to reflect this and embody the ideas in the "stuff" and media of a drawing.'

Article published in The Blue Notebook journal for artists books.Vol 13 No 2.2019.

The Sketchbook and the Collider

IAN ANDREWS

Concentrated in the book.

My approach has been quite diverse involving huge sprawling installations with found objects, sculptures, paintings and drawings. I also make short films and sometimes performance elements appear in the installations leading me in a theatrical direction with costumed actors. The books began when I was convalescing after an operation and I was forced to reduce to a table-top size approach for several months. They were made in ink on folded tissue paper.

The first series called The Circulation of the Sign was an attempt to create a series of images, (moving across categories such as figurative and abstract) that were connected but which could slip and slide in random directions. They attempted to express the disruption of thought processes I had witnessed in my mother when she was suffering from dementia. The phrase, “You remind me of my son,” was both heart-breaking and fascinating as neuronal connections in the brain misfired and thoughts slipped out of factual alignment.

The extreme fragility of the tissue paper and the ridiculous length of some of the books referenced the fragility of the connections between my mother’s thoughts and the long rambling nature of our conversations. The technique: ink seeping through several pages making a series of residue afterimages providing starting points for the next sequence, seemed to embody the decay and change of drawn thoughts.

The books became an intensely concentrated version of my installational practice.

It started with a failure.

The second series of books The shuffle of Things included images drawn in white ink on black tissue paper that bore a striking resemblance to early particle physics cloud chamber images. It was at this point that I responded to a call out from Eastside Projects to work with academics at the University of Birmingham, UK. Small grants were available for a scheme called “Radical Sabbatical” an opportunity to compare research methodologies with a participating academic.

Professor Kostas Nikolopoulos from the particle physics group gave a presentation on the state of current research in particle physics. I didn’t tell Kostas at the time but I had gone to the meeting looking for the chance to work with a particle physicist and I was clutching a couple of my hand-drawn books that most resembled the images of cloud and bubble chamber interactions that had so excited me.

Several aspects from the initial books have proved significant during the subsequent collaboration.

The breaking of logical thought processes into random combinations seems increasingly relevant to the random probabilities involved in particle physics. The method and techniques involved in the production of the books using ink pens and tissue paper has survived into our first exhibited work together and has taken on renewed layers of meaning, (literally.)

I visited Kostas several times at the university to establish some grounds for our potential conversation, and it quickly became clear that although obviously radically different, our specialisms shared the aim of making the invisible visible. Scientific developments have seen the “everyday” dissolve into sub-atomic interactions only accessible by examining traces left in an enabling medium. A process that is mirrored by the artist expressing ideas through marks made and materials manipulated. Taking the same journey from something hidden to something revealed.

It was this shared understanding of trying to expose a hidden reality that formed the basis of our initial proposal. Which was rejected!

Developing the work.

Luckily for myself, Kostas and I had established some kind of rapport and he suggested that we continue the conversation and see where it might lead. I came to the university on a roughly monthly basis and we discussed aspects of particle physics and art. I think his willingness to fit me into his busy schedule was not only due to his interest in art and how different disciplines can inform one another but also because he realised I was keen to learn about particle physics rather than “simply glean a few headline phrases to tag on to an exhibition at a later date” as he later described it.

Two things then happened that moved the project forward. The first was my decision to concentrate on films. This seemed entirely appropriate as the activity in the subatomic realm was all about movement and interaction between particles. Finding artistic equivalents to this process would surely proceed more quickly through moving images!

Kostas introduced me to Simon Pyatt, a technician in the particle physics department who became very enthusiastic about filming some of the equipment in the clean lab. One machine very accurately dispensed tiny amounts of glue that were used to attach electronic circuits destined for the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the European Council for Nuclear Research (CERN). It is considered the European laboratory for particle physics. Simon reprogramed the machine to dispense ink and for a short time the machine made drawings rather than circuit boards that provided some of the earlier footage for the first films. (Rumours that the LHC was late reopening after the winter shutdown due to the late arrival of parts from University are entirely without foundation!). Another machine used wire, thinner than a single human hair to create electronic connections and Simon fitted a microscopic camera to record the connections being made.

The second thing that greatly assisted the project was the development of a series of educational workshops funded by EU creations. I had an educational background and have taught in art colleges for many years. I am committed to educational approaches that forge connections between disparate areas. I have long advocated that Primary school children should be encouraged to develop a “creative curiosity” about the world and then given sketchbooks to record, analyse and discover regardless of whether you label the results art, science, maths or geography.

The workshops were developed with the community arts group I had co-founded with Sarah Fortes Mayer called In-Public. Sarah and I had a range of projects on the go, using art as a conduit to begin difficult conversations. We jumped at the chance to use the visualisation opportunities of art to explain quantum theory to a young audience. The workshops fused an “art school experience” with basic information from particle physics research. Using the main artistic techniques of drawing, sculpture, photography and performance to visualise these hidden particle characteristics and interactions.

It was during the development and delivery of these workshops that I learnt a great deal listening to Professor Nikolopoulos explaining the topic to the General Certificate in Secondary Education (GCSE) pupils.

In addition, the need to find practical artistic equivalents to particle interactions focused my thinking in a very productive way. Professor Nikolopoulos and I have co-authored a paper on the development of the workshops that appeared in the September issue of Physics Education published by the Institute of Physics, IOP.

This project, in marked contrast to my usual practice of accumulation, has involved editing ruthlessly and constantly asking whether any aspects can be discarded. So it was with the development of the films. The first group of films used footage from the clean lab and were themselves a rejection of the initial experiments that involved trying to film movement in the “real world” that would act as an analogy for quantum events: the wave motion created by moving a woven fabric, the reflections on an expanse of water disturbed by ripples and so on. The clean lab footage of the two machines seemed at first a definite advance and it was with great reluctance that I discarded them after the first series was completed. Instead it became clear that the editing process had to become equivalent to the processes in the collider. Therefore the footage being edited needed to be simple so that it revealed the process, and if the process related to the collider, then the footage needed to refer to the sketchbook.

This was made possible by the approach that Kostas and I were now taking. Comparing the material culture surrounding our two specialisms. We focused on a crucial piece of equipment in each case that are used to detect the invisible, make it visible and analyse its significance; the sketchbook and the Collider.

The physicist relationship with their methods and type of detector is fascinating, dividing into the “logic” or “image” traditions, to count or to see. These two approaches fused as the lone builder of equipment in small laboratories transformed into massive Colliders designed, built and staffed by a huge collaborative workforce. The artists’ crucial piece of equipment, the sketchbook, has my contrast remain virtually unchanged since its development during Renaissance.

Despite massive differences the sketchbook and the collider are both arenas where different elements are brought together, sometimes violently, involving “active processes” that create and examine the visible traces of hidden interactions.

So we had two intimate connections between our specialisms. We were both dealing with making the invisible, visible and we both relied on a piece of equipment that was designed to bring together disparate things in the hope of discovering something new. If it appears that I am making the collider feel more personal to the physicist in order to connect it with the sketchbook then the following quote should dispel that:

Detectors are really the way that physicists express themselves. To say something that you have in your guts. In the case of painters, it’s painting with sculptors, it’s sculpture and in the case of the experimental physicist it’s detectors! The detector is the image of the guy who designed it. - Carlo Rubbia,1989

The way was now clear for the first of the resolved films, The sketchbook and the Collider. Which, having discarded footage from the clean lab, I filmed instead the pages of a sketchbook being turned as the basic unit or quanta I was going to use. No extraneous imagery was introduced, merely the turning of pages filled with drawings attempting to visualise particle interactions. The footage was then put through a process designed to mirror the activity within the detector. A unit of footage was created which was sped up over and over again and then overlaid by footage going in the opposite direction, creating a filmic equivalent of a collision event. The result was to some extent random, the final look of the film taking care of itself. The partially random quality referenced the random nature of particle interactions, which are created by probabilities rather than hard and fast laws.

The soundtrack was an accumulation of the actual sounds of the pages being turned and the distortions of that sound as the footage was reversed in direction, and changes made to its speed. Amusingly, a cheap sketchbook had to be used in order to get a satisfactory sound of paper turning through the spiral-bound spine.

Back to the book: Breakout from the book

It now looked as if the project would continue to develop forcefully through the use of moving image work, however the project was about to take a different turn. The university, and specifically Research and Cultural Collections, who fund and administer the various artists-in-residence schemes, including the Radical Sabbatical from which we had been rejected, had become aware of our work. They decided to back the collaboration with a full residency.

Within a few months of the residency commencing an opportunity to show work in the large prestigious Rotunda Gallery in the Aston Webb building at the university became available, and I agreed to take on the challenge even at this early stage. It was not only the daunting scale of the area that proved challenging but also the restrictions on what could be done in the space - that gradually became apparent in discussions with the head of Cultural Collections, Clare Mullet and curator Jenny Lance. A series of proposals were rejected including being able to project films, being able to use any smart screens and being able to use any floor space for three-dimensional work.

This forced me to look again at the hand drawn books that had initiated my approach to Kostas. Indeed alongside the films I had continued to make more hand drawn books, attempting to create a drawing sequence equivalent to particle interaction.

The timescale leading up to the exhibition was short; a matter of weeks, and therefore wide experimentation was not an option. The restriction proved amazingly creative as I took techniques developed in the hand drawn books, the use of tissue paper overlays, allowing several layers to be visible at once, the use of diagrammatic conventions to route the work in a search for equivalents rather than artistic expression, and fused them with the material culture comparisons Kostas and I had been discussing.

Returning to a long held admiration for the work of Paul Klee, I re-read his Bauhaus lecture notes published as The Thinking Eye and decided to expose the mechanics of making a drawing. Revealing the grammar of my visual language in the same way that Professor Nikolopoulos was attempting to expose the basic particles of the standard model. I then sought to find equivalents between the particle characteristics of spin, mass and charge, and the graphic elements of point, line and plane.

The exhibition, The sketchbook and the Collider opened during the Arts and Science Festival at the university and ran until early June 2018. It comprised 3 hand-drawn books, 9 framed layered tissue paper drawings, over 100 drawings applied directly to the wall as site-specific collages and a chart like piece in a large lightbox. The site-specific collages applied straight to the wall referenced particles in their wave configuration and resembled pages from a sketchbook thrown through the air. The framed pieces referenced the process of measurement, which causes particles to locate in particular locations, and the light box piece was a reference to the projections of collision events onto large white tables for human scanners to determine the particles involved in the interaction.

The drawings deliberately used diagrammatic conventions to avoid personal expression and to root the work in an attempt to visualise and establish equivalents. The diagrammatic convention makes us aware that a communication code is in use referencing the data and mathematical equations of the physicist.

Certain rhythms and shapes in the diagrammatic language directly refer to the graph plotting data showing the “spike” of information in an unexpected location confirming the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012.

The drawings use “floating signifiers”, graphic elements with slight variations that can allude to a range of different sources. For example, a series of parallel lines can refer to the edges of the pages of a sketchbook, the rods in the Wheatstone waves machine, a page of text, a graph and both traditional musical scores and experimental graphic notation. The contingent nature of the signs being used echoes the constant transformations and interactions of the particles.

All the drawings were made from overlaying sheets of tissue paper, with no attempt made to disguise this fact. The sheets refer back to the sketchbook and the pages twisting out of shape reference the collisions within the Collider. The pieces made up of many individual sheets allude to the units or quanta, the building blocks of reality.

The paper sheets are often subtly primed, wrinkling the paper and turning it slightly yellow. This draws attention to what would otherwise be a normal sheet of white paper, giving it a certain potential before drawing commences, which references the energy of the Higgs field which is never at zero. It also alludes to the medium needed in the early detectors, the cloud and bubble chambers, to reveal the “jet trails” of particle interaction.

Allusion is made to maps and charts. Another form of visual communication designed to explain and visualise, connected with the idea of measurement and position. Measurement in the quantum world causes the particles, which can also exist as a wave or field, potentially existing anywhere, to locate into one particular position as a particle.

Mapping pins are used as practical fixings but also a drawing element, a series of points. They also refer to the beads of Wheatstone’s wave machine and in addition, connect to the idea of the fixing of a position with its significant consequences in the quantum world.

Looking around the exhibition, it become clear that it was based around the book, either literally: there were three books presented as such but the rest of the show represented a breakout from the book with pages flying free in site-specific collages, pages laid on top of each other in layered configurations and then framed or presented on light boxes to reveal the depth of layers present.

The Historic Physics Instrument Collection

One highlight of my time at the university was a tour of the Historic Physics Instrument Collection by curator Dr Robert Whitworth - including behind-the-scenes access to the stores. It informed my research into the material culture surrounding particle physics and I became particularly interested in two items. The first was Wheatstone’s wave machine, which uses undulating sequences of rods and beads to show how light travels in wave formation. The wave movement is created by the insertion of wooden pro-formers into either end. Invented by Charles Wheatstone (1802 –1875) it was one of a number of philosophical toys that he developed to visualise hidden phenomena. The machine itself is depicted alongside the sketchbook in one of the hand-drawn books, and references to the rods and beads can be found throughout the drawings.

The second item is Hibbard’s disc; a vital component of the Synchrotron, built at the University of Birmingham in 1953 and an example of a particle accelerator.

The disk, designed by L U Hibbard rotated at high speed and controlled the capacitance. A series of tiny mirrors set into the black ring on its surface was used to monitor and control its rotation. A series of photographs of the disk in the Physics Photographic Archive show the simple flat shape in evocative black-and-white photographs as well as images of the Synchrotron when being decommissioned, showing the foundation holes in the floor echoing the shape of the disk itself. The negative spaces act as memories of the positive forms once installed above.

Drawings were made from memory of the photographs and the disk itself. Stencils were cut based on the drawings and were then used as pro-formers, providing guidance and restrictions for mark making activity driven by movement, energy and direction.

Widening the Collaboration

Professor Nikolopoulos has also developed the dance performance Neutrino Passoire, with Mairi Pardalaki, Fanny Travaglino, and Katerina Fotinaki from Paris. This was presented with my film The Sketchbook and the Collider as The Particle Event at mac Birmingham in March 2018. The event showcased a unique three-way conversation between the two artforms and the quantum world, discovering and exploring the commonalities of movement, interaction and making the invisible visible.

In the context of dance and moving image work, my drawing base can be seen both as strength but also a weakness. Movement of the human form to find equivalents to particles seems inherently advantageous, as does the use of computer programming. Both could provide a tighter match between particles interactions and the art produced. The physicists developed Monte Carlo simulations that use the computer to generate random scenarios that can be used to test out possibilities which can seen as a mirror of the sub-atomic reality of particle physics. Artists with a computer programming background could exploit this aspect. My main visual language is the making of marks, the creation of shape and the emergence of form in drawing. (When I make films the drawing base is evident, and even heavily edited footage often has a basis in a filmed drawing.) I can only hope that these restrictions become an enabling, creative factor like the restrictions of the Rotunda Gallery.

A way forward might be shown by recent developments where we have returned to original ideas regarding moving image but in relation to a performance of the drawing activity rather than just the outcomes. “The sound of drawing,” involved the amplification of the sound of the pen moving across the paper during a live performance that also provided footage for a stand-alone film of the same name. This development is in its infancy at present but seems to draw insights from Professor Nikolopoulos's work with dancers Mairi Pardalaki and Fanny Travaglino.

It has been fuelled by the idea that:

The quantum world describes things not as they “are” but as they “occur” and interact. A world not of objects but of events. - Carlo Rovelli, 2015

The first public testing of The Sound of Drawing also involved the participation of the audience, which raised further interesting possibilities regarding interaction.

Professor Nikolopoulos and I have been working together now for over two years and the work shows no sign of abating. I think our willingness to continue is fuelled by our love of cross-disciplinary work and us both seeing the need for “creative curiosity’ to break across boundaries between separate disciplines. Professor Nikolopoulos I know has been impressed by my willingness to change my way of working to accommodate the introduction of new knowledge, and indeed it seemed disrespectful on my part to simply roll out usual methods and approaches in response to the research to which I was generously exposed.

Is this a collaboration or cooperation? Difficult to say.

I produce the artworks following our intense discussions, shared teaching sessions, seminars and presentations, and I take full responsibility for any mistakes in the science underlying what I’ve produced. However the work would not have been made without my relationship with Professor Nikolopoulos and the crucial input he provides, not to mention the support, encouragement and friendship.

Ian Andrews MA RCA, has a diverse practice involving painting, drawing, sculpture and film, often presented in sprawling installations. Reduced, concentrated versions exist as a series of A3 hand-drawn books on tissue paper often over 50 pages long.

Consistent themes involve the primacy of drawing and the importance of “networks structures” in a variety of contexts. Whether neuronal networks that create thoughts in the brain, or the quantum “foam” networks of subatomic structures.

He has recently completed his residency at the University of Birmingham working with the Particle Physics Group and installing an exhibition at the university’s Rotunda space in 2018. He has a solo exhibition at the Library of Birmingham in April 2019.